Daydreaming

Where the idea of building a little cabin came from is pretty

clear. Why it's become such an

obsession is more of a mystery. The "what"--ignoring

all the larger practical questions--is more fun.

--Journal, February 15, 2014

I started this blog after having read Walden for the first time, while feeling inspired to the outdoor life. Over time, I realized that, while I've enjoyed outdoor activities--whether walking the streets and woods or building things on the back deck--I almost never just sit outdoors. I attend to nature, but I do not marinate in nature. If I am outside, I am nearly always doing something. Our next door neighbor, by contrast, is on her back porch much of each day, talking, laughing and listening to music, often with wine glass in hand. She spends much more time outdoors than I do, even though I wouldn't characterize her as a nature-lover. I envy her a little.

The

n, of course, there's the old friend who puts me to shame with her outdoor adventures: hiking the mountains with husband and dog, kayaking white waters and flat waters--and that's just her regular fun. Vacations are saved for week-long excursions into the wilderness. An inspiring life lived for such (literally) mountain-top experiences.

I envy her, too; but I'm not her, having neither her energy nor quite her love of adventure.

I really feel the need to be outdoors, more than do outdoors. But I don't.

Part of this is my fixed habit of relaxing in the quiet of the indoors. Part of it is definitely a desire to be out of the hot sun and not food for mosquitoes. (But drought means there are few mosquitoes, and I still don't relax outdoors.) Part of it may be about "comfort zones": if I'm sitting down, there are nearly always walls around me.

Thinking about all of this led me to wonder if perhaps I wouldn't be more "at home" in nature if I literally had a home in nature: a tiny hut or cabin. A wonderful sister in-law, hearing perhaps of my preoccupations, sent books about tiny cabins and shelters, which I pored over for inspiration.* Ideas emerged one after another at four different scales.

First, the cabin--

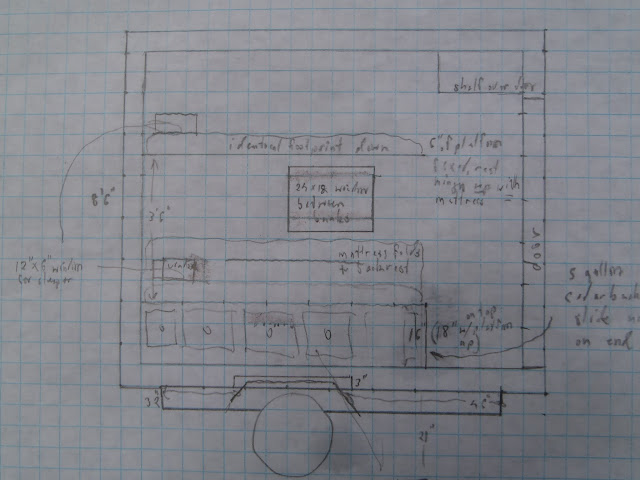

In my mind, the cabin quickly became a daydream of semi-off-grid, small "footprint" retirement. For at least a year I dreamed and drew plans for a cabin based on the "tiny house" idea that has become popular internet fodder: a home built on a large trailer**--both to get around zoning restrictions forbidding a second residence on a property, and to make it possible to pick up and move when the neighborhood gets crowded. The cabin moved in my mind from the middle to the edge of a wood, and it quickly grew to include internet, and bicycle access to groceries and a library. My cabin plans grew and changed as I fit more and more necessities into road-limited dimensions. Some of my drawings were almost detailed enough to build from.

What finally brought drawing to a close was the growing realization that I (meaning we) couldn't live long-term in any such structure, had no place to put it, and had no prospect of raising the money necessary to build it. But I wasn't really sad: it was a lot of fun working out solutions to the challenges of comfortable living in small spaces with limited resources.

By the time I left off with drawing, a six-and-a-half foot wide cabin with solar panels,

a wood burning rocket mass heater,*** composting toilet, and rain barrels filled from the roof,

had grown into a luxurious "Wide Load" of 12 feet by 24, and included a queen-sized loft bed,

cold running water, and perhaps even (gasp!) enough power to run a fridge and freezer.

(Beatrice reminded me she would be living there, too.)

Then the tiny cabin--

My next idea was a

tiny cabin built on the little utility trailer that we already owned.

this would be a sort of all-season shepherd's hut or Gypsy caravan. The

planning and drawings for this got pretty elaborate too, and I felt

that working and sleeping in such a cramped structure (outside footprint

6 feet by about 10 or 12 feet) would force me to spend more time

outside! But calculations showed my little utility trailer wouldn't

handle the weight, and anyway it would just sit in the backyard after

consuming a lot of time and resources.

6X12 all-weather tiny cabin

Floor plan shows overlapping bunk (folds to a bench seat) and desk (hinges down), shelf & counter unit, and heat/cook stove. At bottom is a tiny "mudroom" to keep heat in when going in or out.

End views of interior, bunks folded.

Side views from inside. Lower bunk/bench seat has storage boxes under; bunks have individual windows. Below includes opposite side, showing heater, storage, counter, windows, desk.

Then the micro hut--

A cheap alternative to

the tiny cabin was an even tinier hut, light enough for the trailer, and suitable

for a weekend stay in warmer weather. This was the most restricted and

simple design of the three: it would have a "footprint" of 6X8 feet--the

dimensions of a single sheet of plywood--but gain additional living

volume because the side walls would slant outward, becoming about 6 feet

wide at the top. To save more expense and weight, there would be only

the shell--no inner walls or insulation. Big windows would be okay if the trailer could be turned to keep them out of the hot sun; windows swing out and roof hinges up slightly for ventilation in warm weather. With bunks and desk stowed away, it would feel almost as big as a walk-in closet! It's cartoon-house shape

looked fairly ridiculous and it would have been a bear to move on the

road--about the least aerodynamic shape imaginable. And I am quite proud of it. But I finally couldn't

justify building it, either.

Micro hut: a light-weight, cheap alternative to the tiny cabin

Floor plan shows heat stove & flue later abandoned. Part of lower bunk folds to narrow bench (upper folds flat to wall), desk folds down. Though floor space is only 4X8, slanting walls give almost enough room to swing a dead gerbil. "House that Jack built"-look evident in end view below.

Sketch of inside side view of desk & storage, incorporating two "found" windows.

Finally--

Things were at a standstill. Then a few weeks ago I had a deep think. All I really needed was a sheltered place to sit and read or think in comfort with a drink at my elbow. I could do without shelter from really bad weather if it could at least stand a little rain. Having no walls would mean I would be less separated from nature. To be really useful, it would need to be portable. And best if it didn't take a trailer to move it. To be sure, we already have a 12X12 screen tent, but it's flimsy and difficult to set up, often goes years between uses. So I finally drew a light, open frame of wood with mosquito net walls that could be raised, a light plywood sun & rain roof, and a moveable plywood sun shade. Some lumber, fasteners, glue, paint, an an unconscionable number of work days later, I have my shelter.

Sketch of parts of little shelter--which actually got built

Legs fold down length of frame, to be transported as a 4X8 package.

Roof rests on top and is removable. Walls & ceiling are screened.

It was unofficially baptized a few days ago: I had just installed a table and sat down in comfort, elbows on table, to enjoy the fruit of my labors, when a blue jay eyed me from a nearby tree (vision dimmed by mosquito net), decided there was no danger, and landed a dozen feet away to pick at something in the lawn; a moment after that a squirrel scampered right up to the screen to forage, seemingly unaware of my presence--a moment worthy of Walt Disney.

The screens need to be better worked out, but they definitely need to be moveable.

And any place I relax needs a table for a book, a drink, and a snack.

Okay, molecular cell biology isn't light reading, but at least I'm out here!

*The most inspiring was Derek "Deek" Diedricksen's

Micro Shelters: 59 creative cabins, tiny houses, tree houses, and other small structures.

**Among the cutest I've seen are here: http://www.tumbleweedhouses.com/collections/gallery

***A favorite do-it-yourself technology of off-the-grid types; they're

very cool and worth checking out!