The final installment in my study of three great scientists of the nineteenth century, united by their collegiality, friendship, and their contributions to "the greatest* idea anyone has every had": natural selection. You may wish to read the earlier installments about Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin.

Alfred Russel Wallace was the youngest of the three, so that he was inspired by both Lyell's Principles of Geology and Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle while still in his formative years, and began his fieldwork prepared to believe in "the transmutation of species." He also lived the most interesting and varied life, first becoming known as the co-discoverer of Natural Selection, then one of its chief defenders, an originator of biogeography as a discipline, and then a proponent of directed evolution, of spiritualism, and of social and economic justice. He made substantial and original contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection, and collaborated fruitfully with Darwin for some time. He wrote widely and well on all of these concerns--depending on his writings for much of his income later in life. Though attacked at the time for some of this, he stuck to his guns--even as the science of his time evolved away from allowing supernatural** hypotheses, and away from anthropocentrism, away from a belief that the universe is somehow directed to some goal. Had he not been thus left behind by modern science, Wallace would be much more highly regarded today.

Early life

Wallace began life in straightened circumstances, the seventh of nine children of a father who made unlucky investments, and was victim of unscrupulous men, so that Wallace did not attend school after the age of thirteen. He was introduced to geology through apprenticeship with an older brother to surveying, and learned the rudiments of botany from inexpensive pamphlets produced by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. An enthusiasm for insects came from his relationship with young entomologist Henry Bates, and insects would become both the chief source of Wallace's income, and the means he would use to unravel Natural Selection.

On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart from the Original Type

Wallace's arrival on the world stage when, during his eight years in the Malay archipelago, Wallace's wrote in May 1858 to Darwin to ask him to send along an essay to Lyell, if he thought it worthwhile. Wallace's theory was essentially the same as Darwin's, though Wallace emphasized changes in "conditions of existence" rather than competition among organisms as the motive force of natural selection. In his accompanying letter to Lyell, Darwin declared of Wallace's essay that he "could not have made a better short abstract" of Darwin's own theory. After that, Darwin, mourning the death of his youngest son,*** largely stayed out of the decision-making. Lyell and close friend botanist Joseph Hooker, in a somewhat high-handed**** but honorable resolution of the problem, had Wallace's essay, On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart from the Original Type, presented together with excerpts from Darwin's much earlier (but unpublished) paper, and a letter from the previous year that proved Darwin's priority, at the Linnean Society of London on July 1, 1858. (Though these made no noticeable ripple in the scientific community of the day, Darwin's publication the following year of The Origin of Species surely did.)

Further contributions to evolutionary theory

Beyond "natural selection," Wallace's most important contributions to evolutionary theory were that animals' striking coloration may arise by natural selection that warns predators of its poisonous nature; and that different varieties of the same species may, by natural selection, develop barriers to hybridization that increase reproductive fitness: this phenomenon--still an active area of research--is called the Wallace Effect.

Disagreement with Darwin over "directed" natural selection

Wallace did not believe in traditional religion, but had strong convictions about the centrality of Man in the universe, and that the development of humanity was the universe's highest purpose. Darwin fought him in later years as Wallace began to advocate for divine interference into natural selection at least three times: he believed that the origin of life itself (still a puzzle today) required divine intervention, as did the development of a human mind that (it seemed to Wallace) exceeded that which could be explained by natural selection, and then again to promote the high level of culture in the West that again seemed scientifically inexplicable. This wasn't necessarily a crazy position at the time, since the nineteenth century was a period of gradual movement of the natural sciences away from considering supernatural explanations--because of the intractability of the "species problem,"***** the last of the sciences to do so. Wallace was on the wrong side of history, but not because he was crazy. (This is not the place for a full-throated defense of science's disregard of the supernatural, but if you want to learn a bit, Neil DeGrasse Tyson has a nice lecture illustrated with cautionary tales from science history.)

Further contributions to science

Beyond evolutionary theory, Wallace's work in Brazil and the Malay archipelago (modern day Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia) and the publication of his "Geographic Distribution of Animals" and "Island Life" make him a central figure in the development of biogeography. He documented a line among the islands that separated different groups of species, linked it to the depth of ocean separating them, and explained it by ancient connections among the islands; it is called the Wallace Line. In his mid-fifties, Wallace went on a ten-month lecture and scientific tour of North America beginning in 1887. A week of work with American botanist Alice Eastwood in the Rocky Mountains during this time provided the data to explain commonalities between British and American mountain flora by means of glaciation. He published this in the paper, "English and American flowers." These lectures and investigations became his 1889 book, "Darwinism." His discovery that decades of smallpox vaccination data showed little or no improved survival led him to undertake an anti-vaccination campaign that made him unpopular with the medical establishment, despite using their own data. He argued that deliberately introducing disease (cowpox) into children without clear evidence of positive outcomes was immoral.

Proving a round earth

In an episode you could hardly make up, in 1870 Wallace accepted a five-hundred-pound wager publicized by a flat-earth proponent named John Hampden: to prove that Earth's surface is curved by showing curvature in the surface of an inland body of water. In an elegant demonstration on a straight, six-mile long stretch of canal mutually agreed on, he put targets at fixed heights above the water on two bridges, and mounted a good telescope at the same height on a third. In the telescope witnesses could clearly see that the marks were vertically out of line, with the nearer mark showing above the farther. For good measure, a precise level on the telescope showed that it aimed higher than both distant marks. The degree of curvature shown by this simple experiment over the little six-mile span of water even agreed fairly well with the known curvature of the earth. Unfortunately, Hampden was a rabid biblical literalist, unscrupulous and with a mean streak: not only was the plain evidence denied and the wager not paid, but the man attacked Wallace, slandered him publicly, and continued his attacks even after twice found guilty of libel, fined and even imprisoned. To add insult to injury, Wallace had to take a significant loss in lawyer's fees when Hampden transferred his assets to his family and declared bankruptcy to avoid the fines!

Controversial beliefs

Wallace's scientific interests included Mesmerism, phrenology and spiritualism. Mesmerism (hypnosis) was an interest that Wallace validated experimented in a variety of ways. Phrenology--the hypothesis that features of a person's character were reflected in the detailed shape of the head (reflecting the structure of the brain)--was a popular idea at the time, gaining traction probably by a combination of fuzzy definitions and confirmation bias. Many were take in. Wallace's conviction that spiritualism was real has puzzled historians trying to reconcile it with his undeniably good scientific work. Lately, it has been suggested that Wallace was more willing to buck convention than his colleagues--perhaps less invested in the status quo--as reflected in his early conviction of transmutation of species (which Darwin, by contrast, wrestled with for decades), an abandonment of traditional religion, and his adoption of non-mainstream social and economic ideas, as well as his spiritualist beliefs.

His autobiography makes clear, though, that Wallace saw spiritualism as phenomena well-documented by a good many careful scientists, himself among them. He did not see it as supernatural, insisting that our idea of the "natural" needed expanding. John Nevil Maskelyne's debunking of a spiritualist did not convince Wallace, however. Even today, we see paranormal investigators misled: most scientists are not used to investigating phenomena that are actively trying to deceive them! Professional magicians, such as Harry Houdini in the 1920s and James Randi today, have worked to debunk spiritualism and other pseudosciences. Deception is a magician's stock in trade, making them familiar with techniques and better at spotting it than conventional scientists. These factors taken together make Wallace's convictions seem less strange to me. Wallace's deep conviction that humanity and the human soul was at the center of the universe connect his belief in directed human evolution, social and political activism, and and the our continuation beyond death that underlies spiritualism. In the same vein, Wallace found support in the the apparent centrality of our solar system in the universe. He also deftly destroyed Percival Lowell's canals (therefore life) on Mars--on good evidential terms, but mainly from the conviction that there could be no intelligent life elsewhere.

A late statement of Wallace's religion & philosophy from the end Darwinism contrasts his own with the prevailing mechanistic and purposeless scientific view: "As contrasted with this hopeless and soul-deadening belief, we, who accept the existence of a spiritual world, can look upon the universe as a grand consistent whole adapted in all its parts to the development of spiritual beings capable of indefinite life and perfectibility. To us, the whole purpose, the only raison d'être of the world—with all its complexities of physical structure, with its grand geological progress, the slow evolution of the vegetable and animal kingdoms, and the ultimate appearance of man—was the development of the human spirit in association with the human body."

Yet he goes on to say, "that the Darwinian theory, even when carried out to its extreme logical conclusion, not only does not oppose, but lends a decided support to, a belief in the spiritual nature of man," because natural selection accounts only for the evolution of the human body, but not the spirit.

Economic and social justice and the environment

Wallace's economic and social justice concerns were wide and deep. He had much to say in opposition to the enclosing of commons that gave him some of his early surveying work. He endorsed "equal opportunity" for all, extending this superficially popular idea to an opposition to inherited wealth--since that makes opportunity inherently unequal. He was the first president of the Land Nationalisation Society; favoring nationalization of rural lands, with land being allotted to those who would make best use of it for the public good. He was critical of the effects of free trade on the working poor. He lauded the work of Robert Owen, a social reformer who took a Scottish mill and mill town and remade it in the interests of the workers, reforming the "company store," introducing childhood education to ten years of age, raising standards of health and living, and earning the love of his workforce. He opposed eugenics--which was becoming popular at the time--on the sensible grounds that no one was in any position to determine just who was and was not fit to have their genes passed on. Wallace advocated pure paper currency not backed by gold or silver. He supported women's suffrage; he opposed militarism and believed air warfare should be banned internationally. He was concerned about Man's effects on the environment, and was one of the first, in his 1911 book "World of Life", to say that the ice age megafauna mass extinction was "due to man's agency."

Last years

Wallace never got a permanent job and continued (partly due to risky investments) to struggle financially until given a government pension at Darwin's behest. Characteristically, Wallace insisted in his autobiography that want of money had a good effect, since he was pushed to discover and write and lecture more. Wallace continued his science, social activism and writing til late in life, finally dying at home on December 7, 1913 at ninety.

Nascent natural history interests

Darwin honed his natural history interests partly in competitive beetle collecting as a student, but thought of himself chiefly as a geologist during his travels, experimented with pigeon breeding to gather evidence for evolution and selection, and amidst this became a barnacle expert after a chance encounter with an unusual specimen. Wallace's first encounter with natural history involved an inexpensive little pamphlet on plants, but his friendship with young entomologist Henry Bates led him to insects, and these remained his chief scientific focus ever after, providing both an income and evidence of evolution.

Education

Darwin had a college degree, while Wallace left school at thirteen, and thereafter educated himself; in a sense, though, both men were self-educated, since Darwin was never much interested in the subjects he was supposed to be studying.

Influences

Both men were inspired by Alexander von Humboldt's travels and learned some of their theoretical geology from Lyell; and Wallace was inspired to travel by (among others) Darwin's own "Voyage of the Beagle." Both credited Thomas Malthus' "Essay on the Principle of Population" for the "struggle for existence" that became a key part of Natural Selection.

Travels

Darwin's presence aboard the little ten-gun brig HMS Beagle almost didn't happen: the captain wanted a companion (Charles wasn't technically the ship's naturalist), one of Darwin's teachers recommended him for the post, Darwin's father opposed it, and only the intervention of a beloved uncle saved the day. (At the same time, Darwin was a rather bold adventurer, spending much time ashore and climbing, walking or traveling long distances on horseback--sometimes through regions at war with each other. Wallace was deliberate in his travels, first in the Brazilian Amazon, and then in the Malay Archipelago. (While Darwin's trip was funded by his father, Wallace had a living to make.) Wallace was able to spend much longer in each place than Darwin, who had to adjust his travels to that of the ship.

Conversion to "transmutation of species"

Darwin left port on his five-year circumnavigation an admirer of creationist William Paley and a fairly convinced creationist himself; only entertaining his first doubts when confronted with the distribution of animal species in the different places he visited. He was twenty-two years old. Wallace had the advantage of reading "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a popular and controversial evolutionary hypothesis widely panned by scientists (including Darwin, who thought it devoid of evidence), but a spur to Wallace's imagination. Wallace went to Brazil at age twenty partly for the express purpose of looking for evidence of "the transmutation of species."

Iconoclasm

While Darwin wrestled first with his theory, then the consequences of his theory for religion and society and for his own reputation, Wallace dove straight in. Darwin might never have published****** if not spurred by Wallace's independent discovery. In future years, while Darwin's case was largely argued by others, Wallace--besides being very active in those battles--also adopted socialism, land reform, and other causes that made him unpopular in many circles.

Field work

Darwin's field work was confined largely to his 5-year circumnavigation. Thereafter, he was a homebody, doing lab and garden and greenhouse work at Downe House for the rest of his life. Wallace spend four years in Brazil and another eight in the Malay Archipelago seeking to make a living collecting insects and other animals to send home to well-heeled collectors. He also wrote constantly, using his writings as another source of income. A lecture tour in the US (which Darwin never visited) also added to his income and funded further field work.

Fame

Darwin was widely known and had an enormous correspondence, received popular acclaim for his Voyage of the Beagle, and enormous scientific respect for his multi-volume monograph on barnacles. Wallace wrote much and widely, becoming best known for his travel narrative, The Malay Archipelago. Although many of Wallace's ideas were controversial, neither man lived to see their theory of natural selection accepted by the scientific establishment. (The fact of "descent by modification" (evolution) immediately took science by storm, but the means by which species arose was argued for over half a century.)

Residence

Wallace lived many places (both before and after marrying rather late in life) even in late years, while Darwin settled into Downe House after marriage and remained there for good. As a result of Darwin's illness and inclination, he seldom left it.

Family life

Darwin married his first cousin, Emma Wedgewood, when thirty years old, only a couple of years after the Beagle's return. They had ten children, of whom seven survived to adulthood. Wallace was forty-two when he married Annie Mitten, daughter of a friend who was a moss specialist. (She was likely younger than Wallace, but I couldn't find out by how much.) They had three children of whom two lived to adulthood. Both men lost young children: for the Darwins an infant and a baby, while their beloved Annie died of consumption at age 10 in the midst of his barnacle work (strengthening Charles' turn to agnosticism) while Wallace lost his first born son at the age of 7 in 1874. (I can find no reference to the event in his autobiography, which does not treat of his family.) Both wives survived their husbands.

Health

From soon after his return, Darwin suffered debilitating illness that sapped his strength and often interrupted his work. Despite "hydrotherapy" treatments, the illnesses were lifelong. He died in 1882 at the age of seventy-three. Wallace, despite years in the tropics, lived to a ripe old ninety, surviving well into the twentieth century.

*In the words of the modern philosopher Daniel Dennett.

**Really teleological or "purpose-driven" hypotheses--things are meant by some higher purpose to work out as they have: Wallace himself would not have called them supernatural.

***Charles Waring Darwin, 18 months, died of scarlet fever on June 18th, the very day Darwin sent Wallace's essay along to Lyell. In a June 29th letter to Hooker, he dumps the decision-making in their laps.

****In publishing without Wallace's approval, the men probably broke copyright law of the time, but Wallace never expressed any opposition after the fact. The delay involved in communicating with Wallace back in the Malay archipelago might itself have opened the men to suspicion. And, indeed, associating his work with Darwin's established reputation probably benefited Wallace. Darwin later wrote Hooker in appreciation of Wallace's attitude: "I enclose letters to you and me from Wallace. I admire extremely the spirit in which they are written. He must be an amiable man."

*****The species problem: how do all the species of life arise--each one exquisitely adapted to its place in nature??? --before Darwin & Wallace, no one was able to come up with a convincing non-supernatural explanation.

******Darwin left a sealed essay of his theory with instructions to Emma to publish it upon his death; meanwhile, he continued to build an unassailable case, but never quite looked like he would ever finish.

Sources:

Wikipedia and its links are well-written & probably have as much info as you want.

The Malay Archipelago. Wallace. 1869.

My Life. Wallace. 1905.

The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. 1887. Francis Darwin

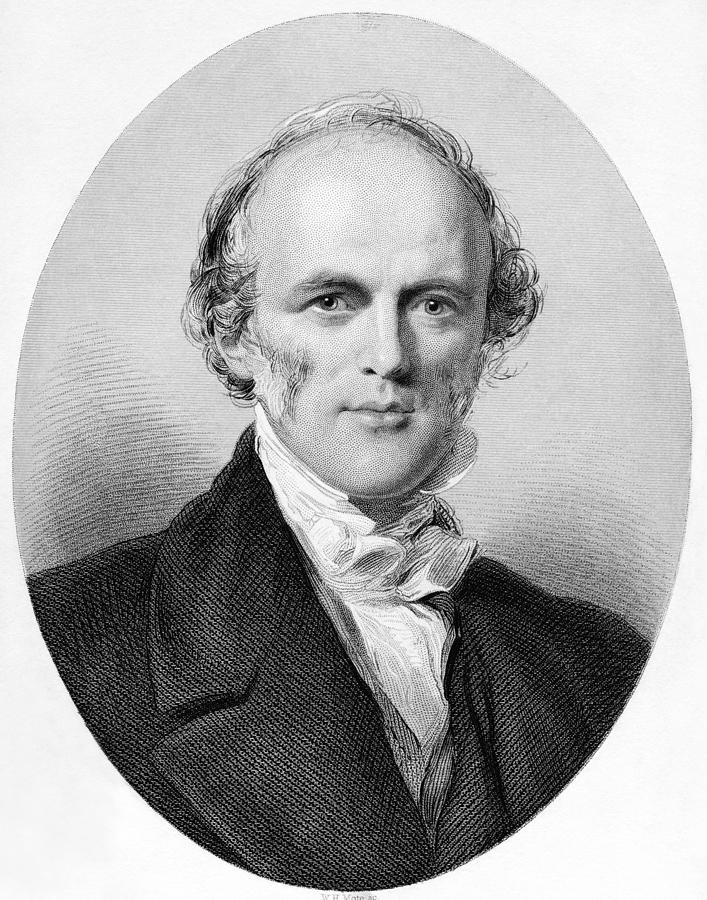

In Singapore, 1862, aged 39.

Statue outside Natural History Museum, London, unveiled in 2013.

Alfred Russel Wallace was the youngest of the three, so that he was inspired by both Lyell's Principles of Geology and Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle while still in his formative years, and began his fieldwork prepared to believe in "the transmutation of species." He also lived the most interesting and varied life, first becoming known as the co-discoverer of Natural Selection, then one of its chief defenders, an originator of biogeography as a discipline, and then a proponent of directed evolution, of spiritualism, and of social and economic justice. He made substantial and original contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection, and collaborated fruitfully with Darwin for some time. He wrote widely and well on all of these concerns--depending on his writings for much of his income later in life. Though attacked at the time for some of this, he stuck to his guns--even as the science of his time evolved away from allowing supernatural** hypotheses, and away from anthropocentrism, away from a belief that the universe is somehow directed to some goal. Had he not been thus left behind by modern science, Wallace would be much more highly regarded today.

Early life

Wallace began life in straightened circumstances, the seventh of nine children of a father who made unlucky investments, and was victim of unscrupulous men, so that Wallace did not attend school after the age of thirteen. He was introduced to geology through apprenticeship with an older brother to surveying, and learned the rudiments of botany from inexpensive pamphlets produced by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. An enthusiasm for insects came from his relationship with young entomologist Henry Bates, and insects would become both the chief source of Wallace's income, and the means he would use to unravel Natural Selection.

On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart from the Original Type

Wallace's arrival on the world stage when, during his eight years in the Malay archipelago, Wallace's wrote in May 1858 to Darwin to ask him to send along an essay to Lyell, if he thought it worthwhile. Wallace's theory was essentially the same as Darwin's, though Wallace emphasized changes in "conditions of existence" rather than competition among organisms as the motive force of natural selection. In his accompanying letter to Lyell, Darwin declared of Wallace's essay that he "could not have made a better short abstract" of Darwin's own theory. After that, Darwin, mourning the death of his youngest son,*** largely stayed out of the decision-making. Lyell and close friend botanist Joseph Hooker, in a somewhat high-handed**** but honorable resolution of the problem, had Wallace's essay, On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart from the Original Type, presented together with excerpts from Darwin's much earlier (but unpublished) paper, and a letter from the previous year that proved Darwin's priority, at the Linnean Society of London on July 1, 1858. (Though these made no noticeable ripple in the scientific community of the day, Darwin's publication the following year of The Origin of Species surely did.)

Further contributions to evolutionary theory

Beyond "natural selection," Wallace's most important contributions to evolutionary theory were that animals' striking coloration may arise by natural selection that warns predators of its poisonous nature; and that different varieties of the same species may, by natural selection, develop barriers to hybridization that increase reproductive fitness: this phenomenon--still an active area of research--is called the Wallace Effect.

Disagreement with Darwin over "directed" natural selection

Wallace did not believe in traditional religion, but had strong convictions about the centrality of Man in the universe, and that the development of humanity was the universe's highest purpose. Darwin fought him in later years as Wallace began to advocate for divine interference into natural selection at least three times: he believed that the origin of life itself (still a puzzle today) required divine intervention, as did the development of a human mind that (it seemed to Wallace) exceeded that which could be explained by natural selection, and then again to promote the high level of culture in the West that again seemed scientifically inexplicable. This wasn't necessarily a crazy position at the time, since the nineteenth century was a period of gradual movement of the natural sciences away from considering supernatural explanations--because of the intractability of the "species problem,"***** the last of the sciences to do so. Wallace was on the wrong side of history, but not because he was crazy. (This is not the place for a full-throated defense of science's disregard of the supernatural, but if you want to learn a bit, Neil DeGrasse Tyson has a nice lecture illustrated with cautionary tales from science history.)

Further contributions to science

Beyond evolutionary theory, Wallace's work in Brazil and the Malay archipelago (modern day Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia) and the publication of his "Geographic Distribution of Animals" and "Island Life" make him a central figure in the development of biogeography. He documented a line among the islands that separated different groups of species, linked it to the depth of ocean separating them, and explained it by ancient connections among the islands; it is called the Wallace Line. In his mid-fifties, Wallace went on a ten-month lecture and scientific tour of North America beginning in 1887. A week of work with American botanist Alice Eastwood in the Rocky Mountains during this time provided the data to explain commonalities between British and American mountain flora by means of glaciation. He published this in the paper, "English and American flowers." These lectures and investigations became his 1889 book, "Darwinism." His discovery that decades of smallpox vaccination data showed little or no improved survival led him to undertake an anti-vaccination campaign that made him unpopular with the medical establishment, despite using their own data. He argued that deliberately introducing disease (cowpox) into children without clear evidence of positive outcomes was immoral.

Proving a round earth

In an episode you could hardly make up, in 1870 Wallace accepted a five-hundred-pound wager publicized by a flat-earth proponent named John Hampden: to prove that Earth's surface is curved by showing curvature in the surface of an inland body of water. In an elegant demonstration on a straight, six-mile long stretch of canal mutually agreed on, he put targets at fixed heights above the water on two bridges, and mounted a good telescope at the same height on a third. In the telescope witnesses could clearly see that the marks were vertically out of line, with the nearer mark showing above the farther. For good measure, a precise level on the telescope showed that it aimed higher than both distant marks. The degree of curvature shown by this simple experiment over the little six-mile span of water even agreed fairly well with the known curvature of the earth. Unfortunately, Hampden was a rabid biblical literalist, unscrupulous and with a mean streak: not only was the plain evidence denied and the wager not paid, but the man attacked Wallace, slandered him publicly, and continued his attacks even after twice found guilty of libel, fined and even imprisoned. To add insult to injury, Wallace had to take a significant loss in lawyer's fees when Hampden transferred his assets to his family and declared bankruptcy to avoid the fines!

Controversial beliefs

Wallace's scientific interests included Mesmerism, phrenology and spiritualism. Mesmerism (hypnosis) was an interest that Wallace validated experimented in a variety of ways. Phrenology--the hypothesis that features of a person's character were reflected in the detailed shape of the head (reflecting the structure of the brain)--was a popular idea at the time, gaining traction probably by a combination of fuzzy definitions and confirmation bias. Many were take in. Wallace's conviction that spiritualism was real has puzzled historians trying to reconcile it with his undeniably good scientific work. Lately, it has been suggested that Wallace was more willing to buck convention than his colleagues--perhaps less invested in the status quo--as reflected in his early conviction of transmutation of species (which Darwin, by contrast, wrestled with for decades), an abandonment of traditional religion, and his adoption of non-mainstream social and economic ideas, as well as his spiritualist beliefs.

His autobiography makes clear, though, that Wallace saw spiritualism as phenomena well-documented by a good many careful scientists, himself among them. He did not see it as supernatural, insisting that our idea of the "natural" needed expanding. John Nevil Maskelyne's debunking of a spiritualist did not convince Wallace, however. Even today, we see paranormal investigators misled: most scientists are not used to investigating phenomena that are actively trying to deceive them! Professional magicians, such as Harry Houdini in the 1920s and James Randi today, have worked to debunk spiritualism and other pseudosciences. Deception is a magician's stock in trade, making them familiar with techniques and better at spotting it than conventional scientists. These factors taken together make Wallace's convictions seem less strange to me. Wallace's deep conviction that humanity and the human soul was at the center of the universe connect his belief in directed human evolution, social and political activism, and and the our continuation beyond death that underlies spiritualism. In the same vein, Wallace found support in the the apparent centrality of our solar system in the universe. He also deftly destroyed Percival Lowell's canals (therefore life) on Mars--on good evidential terms, but mainly from the conviction that there could be no intelligent life elsewhere.

A late statement of Wallace's religion & philosophy from the end Darwinism contrasts his own with the prevailing mechanistic and purposeless scientific view: "As contrasted with this hopeless and soul-deadening belief, we, who accept the existence of a spiritual world, can look upon the universe as a grand consistent whole adapted in all its parts to the development of spiritual beings capable of indefinite life and perfectibility. To us, the whole purpose, the only raison d'être of the world—with all its complexities of physical structure, with its grand geological progress, the slow evolution of the vegetable and animal kingdoms, and the ultimate appearance of man—was the development of the human spirit in association with the human body."

Yet he goes on to say, "that the Darwinian theory, even when carried out to its extreme logical conclusion, not only does not oppose, but lends a decided support to, a belief in the spiritual nature of man," because natural selection accounts only for the evolution of the human body, but not the spirit.

Economic and social justice and the environment

Wallace's economic and social justice concerns were wide and deep. He had much to say in opposition to the enclosing of commons that gave him some of his early surveying work. He endorsed "equal opportunity" for all, extending this superficially popular idea to an opposition to inherited wealth--since that makes opportunity inherently unequal. He was the first president of the Land Nationalisation Society; favoring nationalization of rural lands, with land being allotted to those who would make best use of it for the public good. He was critical of the effects of free trade on the working poor. He lauded the work of Robert Owen, a social reformer who took a Scottish mill and mill town and remade it in the interests of the workers, reforming the "company store," introducing childhood education to ten years of age, raising standards of health and living, and earning the love of his workforce. He opposed eugenics--which was becoming popular at the time--on the sensible grounds that no one was in any position to determine just who was and was not fit to have their genes passed on. Wallace advocated pure paper currency not backed by gold or silver. He supported women's suffrage; he opposed militarism and believed air warfare should be banned internationally. He was concerned about Man's effects on the environment, and was one of the first, in his 1911 book "World of Life", to say that the ice age megafauna mass extinction was "due to man's agency."

Last years

Wallace never got a permanent job and continued (partly due to risky investments) to struggle financially until given a government pension at Darwin's behest. Characteristically, Wallace insisted in his autobiography that want of money had a good effect, since he was pushed to discover and write and lecture more. Wallace continued his science, social activism and writing til late in life, finally dying at home on December 7, 1913 at ninety.

I enjoy comparing and contrasting Wallace with the fourteen years-older Darwin.

Family origin

Though both men technically had origins in the professional class and "new money," Darwin's life was comfortable (especially after marrying his cousin Emma Wedgewood), while Wallace and his family often struggled for financial stability. Wallace was first a surveyor, briefly a teacher, then a collector of exotic animals, an unsuccessful investor, then an author. (Partly by experience, Wallace had far more awareness of and sympathy for the lower classes, and his economic and social justice orientation was partly a result.)Nascent natural history interests

Darwin honed his natural history interests partly in competitive beetle collecting as a student, but thought of himself chiefly as a geologist during his travels, experimented with pigeon breeding to gather evidence for evolution and selection, and amidst this became a barnacle expert after a chance encounter with an unusual specimen. Wallace's first encounter with natural history involved an inexpensive little pamphlet on plants, but his friendship with young entomologist Henry Bates led him to insects, and these remained his chief scientific focus ever after, providing both an income and evidence of evolution.

Education

Darwin had a college degree, while Wallace left school at thirteen, and thereafter educated himself; in a sense, though, both men were self-educated, since Darwin was never much interested in the subjects he was supposed to be studying.

Influences

Both men were inspired by Alexander von Humboldt's travels and learned some of their theoretical geology from Lyell; and Wallace was inspired to travel by (among others) Darwin's own "Voyage of the Beagle." Both credited Thomas Malthus' "Essay on the Principle of Population" for the "struggle for existence" that became a key part of Natural Selection.

Travels

Darwin's presence aboard the little ten-gun brig HMS Beagle almost didn't happen: the captain wanted a companion (Charles wasn't technically the ship's naturalist), one of Darwin's teachers recommended him for the post, Darwin's father opposed it, and only the intervention of a beloved uncle saved the day. (At the same time, Darwin was a rather bold adventurer, spending much time ashore and climbing, walking or traveling long distances on horseback--sometimes through regions at war with each other. Wallace was deliberate in his travels, first in the Brazilian Amazon, and then in the Malay Archipelago. (While Darwin's trip was funded by his father, Wallace had a living to make.) Wallace was able to spend much longer in each place than Darwin, who had to adjust his travels to that of the ship.

Conversion to "transmutation of species"

Darwin left port on his five-year circumnavigation an admirer of creationist William Paley and a fairly convinced creationist himself; only entertaining his first doubts when confronted with the distribution of animal species in the different places he visited. He was twenty-two years old. Wallace had the advantage of reading "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a popular and controversial evolutionary hypothesis widely panned by scientists (including Darwin, who thought it devoid of evidence), but a spur to Wallace's imagination. Wallace went to Brazil at age twenty partly for the express purpose of looking for evidence of "the transmutation of species."

Iconoclasm

While Darwin wrestled first with his theory, then the consequences of his theory for religion and society and for his own reputation, Wallace dove straight in. Darwin might never have published****** if not spurred by Wallace's independent discovery. In future years, while Darwin's case was largely argued by others, Wallace--besides being very active in those battles--also adopted socialism, land reform, and other causes that made him unpopular in many circles.

Field work

Darwin's field work was confined largely to his 5-year circumnavigation. Thereafter, he was a homebody, doing lab and garden and greenhouse work at Downe House for the rest of his life. Wallace spend four years in Brazil and another eight in the Malay Archipelago seeking to make a living collecting insects and other animals to send home to well-heeled collectors. He also wrote constantly, using his writings as another source of income. A lecture tour in the US (which Darwin never visited) also added to his income and funded further field work.

Fame

Darwin was widely known and had an enormous correspondence, received popular acclaim for his Voyage of the Beagle, and enormous scientific respect for his multi-volume monograph on barnacles. Wallace wrote much and widely, becoming best known for his travel narrative, The Malay Archipelago. Although many of Wallace's ideas were controversial, neither man lived to see their theory of natural selection accepted by the scientific establishment. (The fact of "descent by modification" (evolution) immediately took science by storm, but the means by which species arose was argued for over half a century.)

Residence

Wallace lived many places (both before and after marrying rather late in life) even in late years, while Darwin settled into Downe House after marriage and remained there for good. As a result of Darwin's illness and inclination, he seldom left it.

Family life

Darwin married his first cousin, Emma Wedgewood, when thirty years old, only a couple of years after the Beagle's return. They had ten children, of whom seven survived to adulthood. Wallace was forty-two when he married Annie Mitten, daughter of a friend who was a moss specialist. (She was likely younger than Wallace, but I couldn't find out by how much.) They had three children of whom two lived to adulthood. Both men lost young children: for the Darwins an infant and a baby, while their beloved Annie died of consumption at age 10 in the midst of his barnacle work (strengthening Charles' turn to agnosticism) while Wallace lost his first born son at the age of 7 in 1874. (I can find no reference to the event in his autobiography, which does not treat of his family.) Both wives survived their husbands.

Health

From soon after his return, Darwin suffered debilitating illness that sapped his strength and often interrupted his work. Despite "hydrotherapy" treatments, the illnesses were lifelong. He died in 1882 at the age of seventy-three. Wallace, despite years in the tropics, lived to a ripe old ninety, surviving well into the twentieth century.

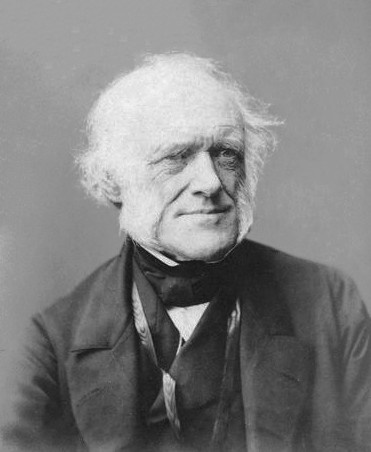

About 1895. aged about 72.

Frontispiece to his 1889 book, Darwinism.

*In the words of the modern philosopher Daniel Dennett.

**Really teleological or "purpose-driven" hypotheses--things are meant by some higher purpose to work out as they have: Wallace himself would not have called them supernatural.

***Charles Waring Darwin, 18 months, died of scarlet fever on June 18th, the very day Darwin sent Wallace's essay along to Lyell. In a June 29th letter to Hooker, he dumps the decision-making in their laps.

****In publishing without Wallace's approval, the men probably broke copyright law of the time, but Wallace never expressed any opposition after the fact. The delay involved in communicating with Wallace back in the Malay archipelago might itself have opened the men to suspicion. And, indeed, associating his work with Darwin's established reputation probably benefited Wallace. Darwin later wrote Hooker in appreciation of Wallace's attitude: "I enclose letters to you and me from Wallace. I admire extremely the spirit in which they are written. He must be an amiable man."

*****The species problem: how do all the species of life arise--each one exquisitely adapted to its place in nature??? --before Darwin & Wallace, no one was able to come up with a convincing non-supernatural explanation.

******Darwin left a sealed essay of his theory with instructions to Emma to publish it upon his death; meanwhile, he continued to build an unassailable case, but never quite looked like he would ever finish.

Sources:

Wikipedia and its links are well-written & probably have as much info as you want.

The Malay Archipelago. Wallace. 1869.

My Life. Wallace. 1905.

The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. 1887. Francis Darwin