This will NOT be my usual post of observations in suburban natural history. But it IS a post I'm itching to write!

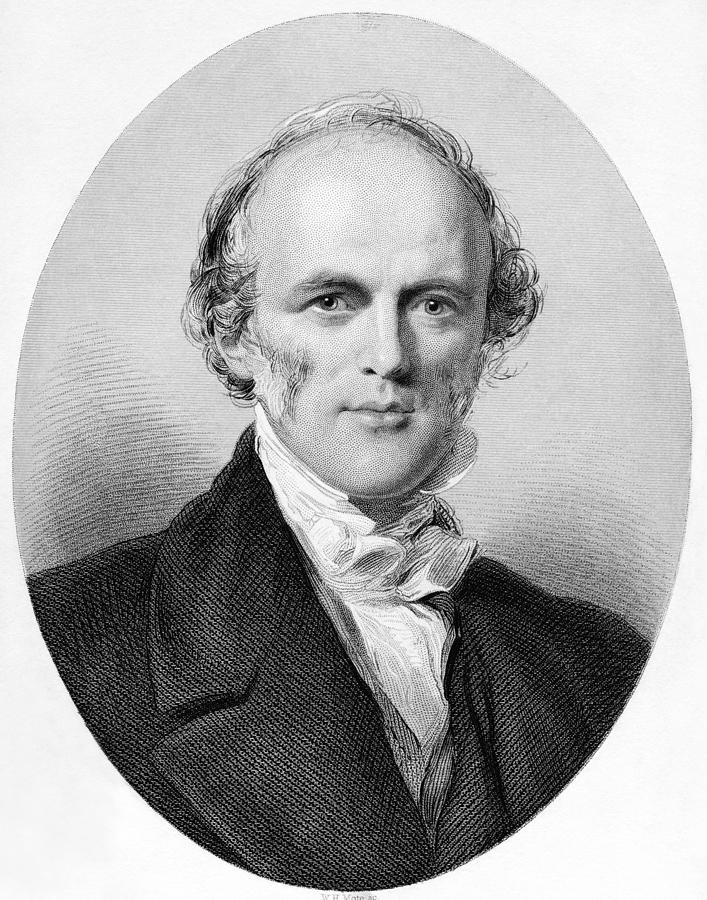

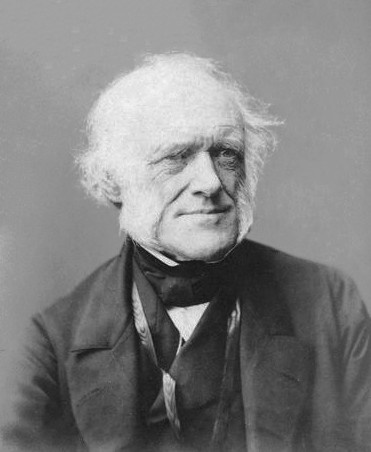

Owing to my "discovery" of FREE electronic books after receiving an e-reader for my birthday, I have been immersed of late in the world of Charles Darwin. I hadn't read his Origin of Species, and the journals of his round-the-world voyage since I was an undergrad, so I downloaded both and started in on the Journal. I emerged a month later with a new appreciation for Darwin the Geologist (which is how he thought of himself) and quickly turned to Charles Lyell, the author of the three-volume Principles of Geology that came out around the time of Darwin's voyage and became both a major resource for Darwin, and a classic of the science in its own right. (The Beagle's captain, Robert Fitz Roy, presented Darwin with the first volume* as a gift, and Darwin had the remaining volumes shipped to him during the five-year voyage.)

I plowed through Principles of Geology over Christmas break, learning much about the state of science in the middle of the nineteenth century. Lyell included a good deal of history and biology in his book, and--despite a scientific open-mindedness that sometimes surprised me--revealed some of the attitudes and biases of Victorians in his writing.

Thinking about these two, their friendship, the encouragement Lyell gave Darwin on publishing his theory of species evolution, and yet Lyell's disbelief in Darwin's theory, I turned for the first time to the "other evolutionist": Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace is credited with arriving at very much the same theory as Darwin, and spurring Darwin to finally publish his "little book"--after decades of dithering--so that he wouldn't lose his priority of discovery. In my scanty memory of science history, Wallace isn't credited with much else, but he certainly deserves to be.

I will take these men in roughly chronological order, devoting this post to Charles Lyell.

Lyell was a lawyer, but also a man of means able to travel freely. He was both a scientist** in his own right, and a great theorist and compiler of information. His Principles is comprehensive, but is not a field manual. (Darwin learned his rocks, strata, and the like as a college student--though almost entirely unofficially.) The picture of 19th century science I get from reading Lyell ranges from science's attitudes toward religion, to white supremacist notions of Victorians, to the details of physical geography and stratigraphy.

I will take the science first. Lyell was a chief proponent of Uniformitarianism: the idea that the earth's surface was formed by ordinary processes that had occurred over long periods of time. ("Deep time"--uncertain in extent, but probably measured in millions of years--was a break from the biblical timeline of 6000-odd years made popular by Bishop Usher.) Uniformitarianism is often summarized: "the present is the key to the past." The opposing camp believed that vast catastrophes had shaped the earth in olden times (often equated with biblical events such as Noah's flood), leaving us a landscape that could not be explained by present experience. It was the consensus opinion that many species of ancient life were now

extinct, and Lyell was one who believed extinction to be a normal part

of earth history, rather than resulting from catastrophes. Uniformitarianism was on the ascendancy, and modern geology traces its understandings mainly to it, though acknowledging that catastrophes DO sometimes happen: enormous volcanic eruptions and asteroid strikes, for example.

Geologists, aware of the power of erosion to wear down the landscape, was very much concerned with understanding how there could still be mountains on an old earth. At the same time, commonplace knowledge of strata bearing sea shells found high in the mountains begged explanation. Much of Lyell's second volume is reports of land that have risen or sunk in historical, or recent prehistorical, times. Much of this work is very ingenious. For example, a Greek ruin included pillars that showed evidence of damage by marine life, and historical reports of their being sometimes on dry land, other times in shallow water; Lyell interprets this as evidence that that landscape had fallen deep enough for the pillars to be completely submerged since they were built, and risen and fallen several times more recently. He discusses many instances of coast that has sunk and been destroyed by the sea, including loss of whole villages in Great Britain. He finds strata with marine fossils elevated above sea level, interpreting the age in which the land rose according to how many of the fossils matched creatures still living: the more that matched, the more recent the uplift. (Geologists knew that lower rock strata in a series were older than higher strata, but had no way to know just how old any strata were.) What causes the rising and falling of the earth's surface? Lyell describes several hypotheses, some laughable until you realize that no one had any idea what lay below earth's surface beyond evidence that it was hot and molten in places. He does not pretend an answer, but finds it pretty clear that earthquakes and volcanoes are somehow related to each other, and intermediate causes for some of the motion. (Not until just fifty years ago did we really begin forming a comprehensive picture, the theory of plate tectonics.)

Lyell's entire third volume is devoted to living species, what they are, their geographic distribution, and the question of their origin. His understanding of ecology is very respectable. He has clear notions of how species grow, decline and change their distribution in response to their physiological requirements, changes in conditions, and the influences of other species--whether competitors or predator/prey. Except for terminology, Lyell could almost have taught the introductory ecology class I took in college. He spends a good deal of time and ink first explaining Jean Baptiste Lamarck's evolutionary theory (now remembered as the first, but flawed, truly evolutionary theory) and then takes him apart with a very sharp scalpel. He got my full attention when he turned his gaze on variation: the raw material of Darwin's Evolution by Natural Selection that would burst upon the world only a few years after this particular edition of Principles came off the presses. Lyell showed evidence that variation was not the bottomless well Darwin needed, but had built-in limits. He gave instance after instance of animals brought under domestication, bred in various direction, and then hitting a wall after they ran out of variation. I wondered how Darwin would answer this.***

Of course, genetics was a black hole until the 20th century. Many observations showed that offspring had characteristics of their parents and sometimes other ancestors, and that individuals varied. But there was no clear mechanism to explain this. (Gregor Mendel, hard at work crossing peas in his monastery garden, would publish in an obscure journal no one would read for decades. He it was who discovered genes.) So ideas like "inheritance of acquired characteristics" (Lamarck) were far from dead letters; Darwin entertained some unlikely theories of inheritance himself, and considered Lamarkian ideas possibly valid in late editions of his Origin.

Science in Lyell's day was in the middle of a slow evolution. Physics and chemistry had long since stopped invoking the "God hypothesis" to explain their observations. The other natural sciences were following, but biology was lagging behind--in part because no one could come up with a plausible way to explain how living things could be so closely adapted to their situations without being designed so. (Of course, even today there are those who can't accept it, but it's no longer a scientific problem, just one of human nature.) Lyell himself looks hard for natural explanations for things, but still occasionally reaches for a teleological**** explanation. "It seems, also, reasonable to conclude, that the power bestowed on the horse, the dog, the ox, the sheep, the cat, and many species of domesticated fowls, of supporting almost every climate, was given expressly to enable them to follow man throughout all parts of the globe, in order that we might obtain their services, and they our protection." And the last few paragraphs of his Principles is a kind of credo. "But in whatever direction we pursue our researches, whether in time or space, we discover everywhere the clear proofs of a Creative Intelligence, and of His foresight, wisdom, and power." Not until the dawn of the 20th century would science finally refuse to settle for supernatural answers.

The Victorian Lyell displays what I think a remarkable open-mindedness. At one point he muses upon the future of humanity; he expects that humanity, as one among many species that have come and gone, will eventually become extinct as they have. Later, in the realm of ecology, he points out that a natural landscape brought into cultivation--increasing its productivity for us--might very well be less productive for wildlife, making it at best a mixed blessing in the whole scheme of things. "It admits of reasonable doubt whether, upon the whole, we fertilize or impoverish the lands we occupy," he writes. Though he is aware of human-caused extinction, on the other hand, he seems to believe that it is our destiny--like that of many successful species before us-- to dominate and modify the face of nature. (Of course, he could have little way of knowing what a hash we would make of it.)

I will leave discussion of Lyell's attitude toward imperialism and other races for another post, since it was one shared by other protagonists.

*This first volume was devoted to a history of geological ideas, going all the way back. I suspected it would be a snoozefest. It wasn't.

**Science at that time was not a profession; so most scientists had day jobs. Many were clergyman, since the study of natural history was encouraged with the idea of learning about God from His creation. Darwin came from a landed upper-middle-class family (at one point preparing for the ministry himself) and married his first cousin Emma Wedgewood (yes,

that Wedgewood family), making him a man of leisure. --though to his everlasting credit he worked very hard his whole adult life at his chosen vocation, making many discoveries which were eclipsed by his theory of evolution.

***Today we know that we inherit genes from our parents in the form of molecules of DNA that encode information, and that this DNA accumulates code variations randomly over time as chemical changes called mutations. So although a particular population of domesticated animals really can "run out" of variation in the short term, mutation will continue to add more variation to the gene pool in the long term.

****Teleological explanations are about

purpose; things are the way they are because they are means to some end. For example, dogs have so much variation

because that enables them to be bred to many different uses. This is simply another way of saying it was "designed" that way. (Lyell himself discusses a much more reasonable alternative hypothesis: that domestication didn't "work" on any animal that didn't start with enough variation to make useful breeds--such attempts were early abandoned and not recorded.)